The Oedipus myth has everything you need for a gripping tale: a deadly prophesy, a paranoid king, a big secret, a murder, a suicide…

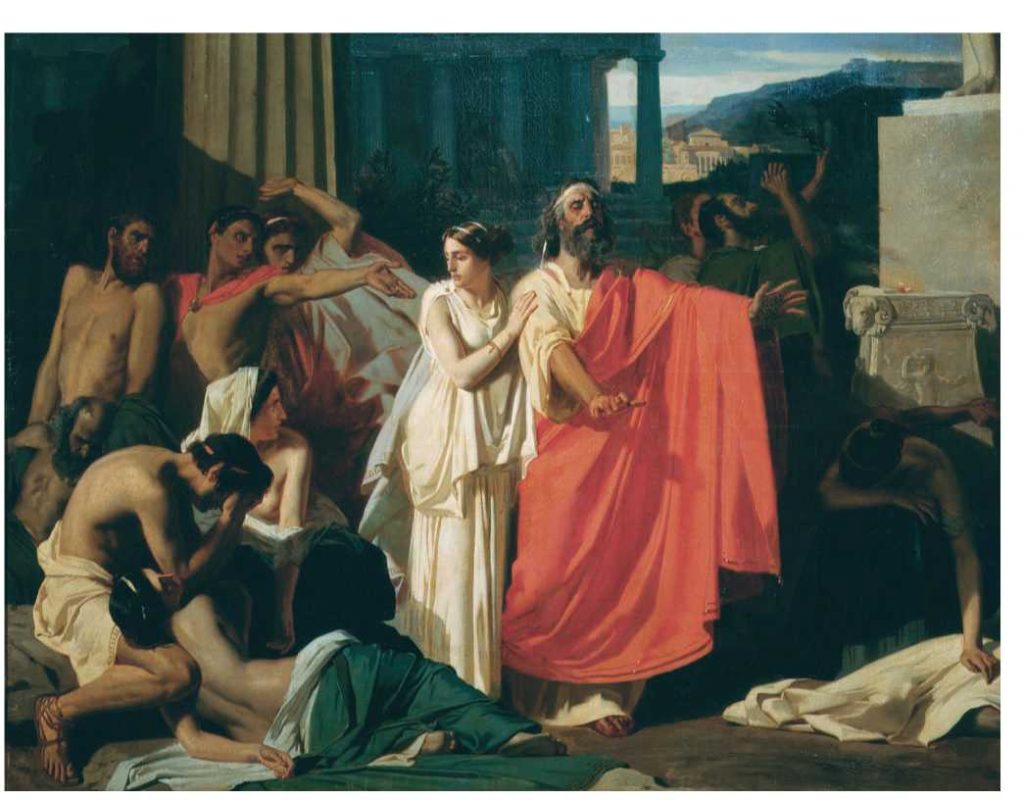

The problem, however, is that very little actually happens between the set up, pay-off and denouement. At the start we have the prediction that the royal baby will grow up to murder his father and marry his mother, eighteen years or so later the prophesy comes true, fifteen years or so after that the truth comes out. For such a dramatic concept it’s not exactly edge of your seat stuff. In the first of the Theban trilogy, Sophocles focuses on the last of those eras, with Oedipus playing detective trying to uncover the old king’s killer in order to lift the plague on Thebes, only to discover he himself is the killer. This approach, whilst effective, entirely relies on the audience’s familiarity with the myth to create the frisson of dramatic irony so essential to the play’s tension. And it didn’t help me much anyway as I wanted to focus on Jocasta’s journey, how she dealt with a series of emotional blows punctuating a life at the apex of government.

So it wasn’t long before I realised this musical was going to be a lot harder than I thought (and I already thought it was going to be hard). I was prepared to play fast and loose with the story – like the Coen Brothers’ Oh Brother Where Art Thou? does with Homer’s Odyssey – but whilst The Odyssey is a thrill-a-minute action saga, in Oedipus the three key plot points happen decades apart. How is a writer supposed to sustain momentum when the biggest stage direction is “years pass”?

The other big problem: The Sphinx. The last thing I wanted in my serious musical was a riddling monster. Especially one with such a crap riddle.

After much thought I realised the solution to the former came with the adaptation of the latter.

My idea for the overall treatment of the musical was rooted in a simple question: What kind of realistic set of events could, after the passing of multiple generations, be mangled and manipulated into our current Oedipus myth? And since the later Theban plays see Jocasta’s brother Creon take the throne (who is far easier to view as an actual villain rather than just a troubled ruler) then we can safely assume that any subsequent spin would be in his favour. If the Oedipus story has any factual basis (and I’m not saying it does, but if) we must suppose actual monsters (of the taloned, half-human, half-lion variety) were no more real in the past than they are now. Our monsters these days are political: they are part fact, part fear and usually shrouded in propaganda. So if we are told of a monster that terrorises a kingdom it seems pretty obvious that the monster is probably some kind of political movement.

And so those difficult gaps in the original myth suddenly become space to tell the story of Sphinx – how an increasingly paranoid king squeezes and squeezes the population with anti-union laws, night raids, bans on assembly etc and in so doing inspires an underground movement (originally non-violent and then increasingly militant) that works against him. What I didn’t anticipate was that this would become one of the major narrative threads, that Sphinx didn’t have to be some plot-point for the classical characters to dance around, it could be a big part of the story, mirroring the troubles of the central relationship with a peoples’ movement that could explode at any moment. In the original myth Oedipus is the ticking timebomb – in this musical version it’s the people who are the timebomb.

When I began properly fleshing out the narrative David Cameron was Prime Minister. Yuck, I thought, what a hideous slippery individual, the very embodiment of smug entitlement. He’ll do as my King Laius: a moist, red-faced, simpering balloon. Fine. I’d already decided to make media manoeuvrings and political spin into big themes – I liked the idea that politicians would use the scandal of royal incest as a way to deflect criticism elsewhere. So far so horrible. But despite there being a despicable system with despicable minions there was no actual villain. King Laius isn’t a villain, he’s just an unlikable victim. Fate is the real threat but it’s difficult to Boo at a concept. I needed some sort of Iago character to sneak about and soak up the hideousness of everything. Enter Creon, Jocasta’s brother, a supporting character in Oedipus Rex who properly comes into his own later in the Sophocles trilogy. I’ve made him into Laius’ old school friend and political advisor – imagine if Humphrey from Yes Minister was even more manipulative, murderously so. But where does this family come from? Another bit of dramatic license: I’ve given Jocasta and Creon a father (yes, they have a father in classical mythology – Cadmus, one of the early Greek heroes – but not one who features in the Oedipus story) – this man is self-made, new money, a threat to the old order as well as a threat to the new, he is a newspaper tycoon, he is basically Rupert Murdoch. So that’s my set-up: Media marrying Monarchy and the world going up in flames.

But man, it is not easy keeping your villains villainous these days. My second draft had to really push the ridiculousness of those characters once Trump came along. And the phenomenon of Brexit made my already relatively cartoonish sequences depicting press immorality seem like an old episode of Newsnight.

That’s the biggest tragedy in all this. Some of the characters depicted in this musical are so utterly rancid in what they are prepared to do to assert power, yet next to the people in government they actually seem quite credible. Musicals are supposed to feature larger than life characters but how can anyone be larger than Donald Trump (the size of his hands notwithstanding)? It’s an ongoing difficulty for satirists but probably the least of our worries right now.

Still, at least my musical has one thing going for it – I get to make these hideous people suffer. A lot.

BACK TO MAIN JOCASTA PAGE

Read an article about composing the songs

Read an article about writing the script

Read an article about the studio team

Read an article about recording the rhythm section

Read an article about recording the singers

Read an article about the orchestration

Read an article about recording the crowd vocals

Read an article about mixing the album

View photos from the Lowry showcase event

View rehearsal photos

Project Overview / Final Thoughts

And here’s a piece about being funded by Arts Council England