If I were to say “I’m writing a novel” I expect people would mostly respond with “What is it about?”

When I mention I’m writing a musical, however, the most common response is “Do you have funding?”

Maybe it’s just the company I keep. Almost everyone I know seems to be in a constant state of application angst, totting up projected expenses for arts council bids, bombarding their social media feeds with kickstarter campaigns, trying to work out if there’s any kind of community outreach slant they can put on a new project so that it meets the criteria for some glittering new grant…

I’ve been avoiding the funding question ever since I started this musical. Though I will certainly do my best to secure the budget for a full-scale production when/if the time comes (or at the very least a soundtrack album) this project was always designed to be for me. I want to finish writing the thing before I think about selling it – just seems more sensible that way round. This is my hobby away from all the admin associated with DIY labels and DIY music careers. Those two things were supposed to be glamorous enough to balance out the mundanities of British life. But everything becomes normal if you let it. And I let it. I wrote about three songs last year in between doing the booking and PR for Debt and The Bedlam Six. Then when I started working on the musical I wrote sixteen songs in eight months. I feel completely rejuvenated.

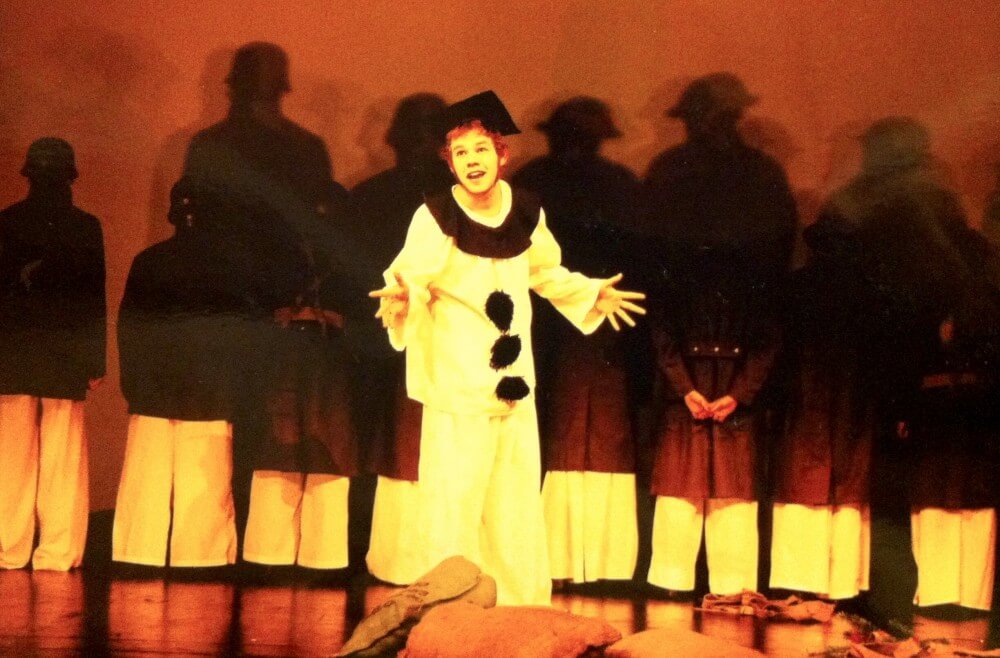

I’ve been talking about writing a musical for over a decade. My background is in theatre. That’s me in the photo above, playing the MC in Oh What A Lovely War. I love the artificiality of theatre. I love how the audience is in on the deception. Pop music would be much the same but for the fact that everyone involved is generally trying to con everyone else – critics and audiences are forever discussing the idea of artists laying themselves bare, of uncovering truths, of expressing their feelings when most of them are only peeling off one mask to replace it with another (similar to what we all do in everyday life I suppose). Imagine going to see A Midsummer Night’s Dream and discovering that the person next to you actually believes fairies have replaced a man’s head with that of a donkey’s. You’d say “no, look, you can clearly see it’s a costume” as they rock back and forth gabbling incredulously. Then go to a music venue and watch the strutting geniuses emoting furiously into their microphones for a nice tidy ninety minutes, the front row swooning into the arms of security guards. Theatre isn’t the only place that’s full of asses.

The second most common response to me mentioning my musical is “Oh I must admit I’m not really that keen on musicals.”

Well I must admit I’m not really that keen on BAD musicals either. Musicals used to be churned out with the conveyor-belt regularity of B-movies and spam. But the good ones, the REALLY special ones transcend time. Productions like Singing In The Rain, Oliver!, Cabaret and The Blues Brothers have little in common but share one key attribute beyond the use of songs – they are all about periods of transition (in these instances struggling severally with modernism, technology, political ideology/extremism, poverty, exploitation, popular culture and redemption). This is what the musical excels at – those absurd, almost surreal explosions into fantasy throw a warped reflected light on the real life that spawns it.

People aren’t all that surprised I have ambitions in this area. Most reviews of my work mention theatricality (some positively, others less so) and I was initially under the impression that writing a musical would be a way of giving that side of my brain free rein for a while, to really indulge the ideas that would ordinarily be scoffed at by the po-faced music press as overly self-indulgent. Once I got going, however, I found that I was being more drawn towards a conventional pop bent – writing quickly and simply, not over-egging metaphors or trying to be showy or clever. Songs about one thing, one thought, one idea – statements of intent or reaction rather than the self-reflexive peregrinations I’m often guilty of. Perhaps one of the reasons I’m finding this project so liberating is that there is very little irony at work. Most of the songs I write for the Bedlam Six contain a hefty dose of cynicism, indeed I tend to embed the seeds of a song’s undoing within the song itself, probably as an unconscious way of deflecting criticism. But here there are characters that have their own ideas; my go-to cynicism does not fit with the dreams and opinions and ideologies of this cast of characters, they’ve got bigger worries than me. It’s been quite an invigorating experience writing songs about optimism. Besides, there’s no need to temper a song’s hopeful resonance with doubt, the events that follow will provide their own ample balance soon enough – some songs are light, some are shade, there’s no need to be overly academic when dealing with the spectrum of emotions. And for once it’s not all about me. Indeed, one of the reasons I wanted to write a musical was that I longed to create something that could stand on its own two feet. Bedlam songs are only songs when we play them. They’re like trousers and shirts, they don’t look like anything when they’re not being worn, just a flop of rags. I wanted to make something more like a hat or a pair of shoes – something that keeps its shape, something that doesn’t need me to inhabit it. Something that I can ultimately walk away from – or indeed something that might walk away from me.

So what is it about?

This is where the eyes start rolling.

My musical centers loosely on the story of Oedipus (by the way, the third and forth most popular responses are “Does it feature your song Mother?” – no, that song actually has nothing to do with mothers – and “have you heard Tom Lehrer’s song about Oedipus?” – yes, but I think after sixty years the rest of us are allowed to have a go at that subject without upsetting the culture police). There have been a handful of attempts to make this story into a musical over the years, mostly small-scale fringe productions playing it for laughs. The fact that the typical reaction to the Oedipus myth is one of amusement just goes to show how horrifying we must all think it is. And it is for that reason I wanted to tackle it. And not as a comedy. This is arguably the greatest of all the tragedies – nowhere else is the concept of Fate as universal villain so utterly, irredeemably, ruthlessly hideous.

Oedipus himself is a pretty tedious protagonist though. So passive. That’s why I’m concentrating on Jocasta, his mother. She is just as cursed as he is, more so even. The version I’m writing focuses on her transition from naive trophy bride to reluctant steward and finally to powerful doomed regent. She is very strong and she is very flawed. There are a lot of songs about hope. And, inevitably, hope dashed. It’s set in a sort of alternative 30s Britain, kind of like if we’d had the Spanish Civil War here. It’s a bit of a historical/cultural smorgasbord though, I’m keen to throw in a more contemporary view of politics and spin doctoring, the classical Greek Chorus in this instance being members of the gutter press and braying backbenchers. It’s all going to be pretty bleak and I doubt Cameron Mackintosh will be knocking on my door any time soon.

But just because we’re all going to die doesn’t mean we can’t make a song and dance about it.

In fact there’s every need to make a song and dance about it.

But no quantity of absent friends could stop me enjoying the Bury concert. It was definitely the most surreal yet.

But no quantity of absent friends could stop me enjoying the Bury concert. It was definitely the most surreal yet. When I arrive I survey the scene, instantly noticing the climbing frame and slide. I make a quick weight calculation and decide not to incorporate it into my act. Sorely tempted though I am.

When I arrive I survey the scene, instantly noticing the climbing frame and slide. I make a quick weight calculation and decide not to incorporate it into my act. Sorely tempted though I am. And off I go, beginning with a song about dying in a brothel. Well the children have to learn about these things some day, it might as well be from me. It’s not long before the parents and offspring have split into two distinct groups, facing each other like armies on opposing hilltops during the Napoleonic Wars, me in the middle to-ing and fro-ing like a lost serf. The children dash away when I hop too close but soon learn that, like an uppity spider, I’m actually more afraid of them than they are of me. Emboldened by their greater numbers they chase me around the garden like a pack of wolves encircling a bewildered sheep. I’ve been told they can smell fear, they are clearly thirsty for a kill. I bargain for my life with a song about an immortal dog. They show clemency and permit me to finish my set unharmed. For now.

And off I go, beginning with a song about dying in a brothel. Well the children have to learn about these things some day, it might as well be from me. It’s not long before the parents and offspring have split into two distinct groups, facing each other like armies on opposing hilltops during the Napoleonic Wars, me in the middle to-ing and fro-ing like a lost serf. The children dash away when I hop too close but soon learn that, like an uppity spider, I’m actually more afraid of them than they are of me. Emboldened by their greater numbers they chase me around the garden like a pack of wolves encircling a bewildered sheep. I’ve been told they can smell fear, they are clearly thirsty for a kill. I bargain for my life with a song about an immortal dog. They show clemency and permit me to finish my set unharmed. For now. It was a real blow when, after two weeks on the road together, Felix had to bow out of our house tour. He’s had some distressing news from abroad and, though the crisis is now over (mercifully with all concerned completely recovered), he understandably wants to be where he is needed most.

It was a real blow when, after two weeks on the road together, Felix had to bow out of our house tour. He’s had some distressing news from abroad and, though the crisis is now over (mercifully with all concerned completely recovered), he understandably wants to be where he is needed most. I got in touch with long-serving comrade in cynicism

I got in touch with long-serving comrade in cynicism

Richard was up first. He’s not played publicly since last year but you’d never guess; he’s a natural entertainer. At one point he prefaces a song with reference to the vernal equinox and then gets into a hilariously furious exchange with one of the audience about whether or not he actually means solstice and whether it really matters. As heckles go it was certainly one of the more learned.

Richard was up first. He’s not played publicly since last year but you’d never guess; he’s a natural entertainer. At one point he prefaces a song with reference to the vernal equinox and then gets into a hilariously furious exchange with one of the audience about whether or not he actually means solstice and whether it really matters. As heckles go it was certainly one of the more learned. CRASH

CRASH

and percussion. During soundcheck I was terrified of breaking something. Anyone who’s seen us perform will know I like to jump about a fair bit, well here I was in severe danger of smashing something precious with every leg kick and foot stamp, nestled as we were between a sousaphone, a bouzouki, violins, more accordions/concertinas/melodeons than I’ve seen outside of a music shop plus all sorts of paraphernalia.

and percussion. During soundcheck I was terrified of breaking something. Anyone who’s seen us perform will know I like to jump about a fair bit, well here I was in severe danger of smashing something precious with every leg kick and foot stamp, nestled as we were between a sousaphone, a bouzouki, violins, more accordions/concertinas/melodeons than I’ve seen outside of a music shop plus all sorts of paraphernalia. crawling up my sleeves. The midges too.

crawling up my sleeves. The midges too. myself in perspiration over the course of the set.

myself in perspiration over the course of the set.

Warrington’s gig was more of a house festival than a house concert, the garden having been transformed into a miniature Worthy Farm. There was a little gazebo with a sign saying “Woodland Stage” and all sorts of decorations. They’d even made wristbands! In keeping with the grandeur we set up our little PA system for the first time this tour.

Warrington’s gig was more of a house festival than a house concert, the garden having been transformed into a miniature Worthy Farm. There was a little gazebo with a sign saying “Woodland Stage” and all sorts of decorations. They’d even made wristbands! In keeping with the grandeur we set up our little PA system for the first time this tour.

Felix was up next.

Felix was up next.

Felix is up first. He does not shy away from audience participation, at one point even enlisting the skills of two drummers to accompany him in a song about demonic sex. For his finale he succeeds in reversing the usual backing vocalist gender stereotypes by getting all the men to sing falsetto and the women to growl the baritone. It works. It shouldn’t but it does.

Felix is up first. He does not shy away from audience participation, at one point even enlisting the skills of two drummers to accompany him in a song about demonic sex. For his finale he succeeds in reversing the usual backing vocalist gender stereotypes by getting all the men to sing falsetto and the women to growl the baritone. It works. It shouldn’t but it does.

Yes, Salford’s concert was in a garden. Good to get out in the open air at last, we’ve been sorely lacking in vitamin D for the most part of this tour. And what a beautiful sunny day for a barbeque. Greater Manchester was certainly doing its best to do away with all those rainy stereotypes. Did you know the name of Salford derives from the Old English word Sealhford, meaning a ford by the willow trees (referring to the sallows that used to grow along the banks of the pre-industrial River Irwell)?

Yes, Salford’s concert was in a garden. Good to get out in the open air at last, we’ve been sorely lacking in vitamin D for the most part of this tour. And what a beautiful sunny day for a barbeque. Greater Manchester was certainly doing its best to do away with all those rainy stereotypes. Did you know the name of Salford derives from the Old English word Sealhford, meaning a ford by the willow trees (referring to the sallows that used to grow along the banks of the pre-industrial River Irwell)?

House concerts are different though. Every single one is a party and every person present becomes a friend. They might seem a lot milder as a concept: people sitting in someone’s living room listening to folk music with unostentatious little bowls of nuts, crisps and carrot batons distributed at sensible distances (the most volatile moment that springs to mind was when we got into a moderately heated debate about why Stephen Sondheim was overrated). But manners and mezze platters aside we’re basically doing a tour of parties and it’s easy to let the booze consumption creep up when you’re not really paying attention to how often someone is refilling your wine glass.

House concerts are different though. Every single one is a party and every person present becomes a friend. They might seem a lot milder as a concept: people sitting in someone’s living room listening to folk music with unostentatious little bowls of nuts, crisps and carrot batons distributed at sensible distances (the most volatile moment that springs to mind was when we got into a moderately heated debate about why Stephen Sondheim was overrated). But manners and mezze platters aside we’re basically doing a tour of parties and it’s easy to let the booze consumption creep up when you’re not really paying attention to how often someone is refilling your wine glass. We were rewarded for our evening’s efforts by not one but two actual beds in not one but two separate bedrooms. If this luxury continues I might turn into one of those insufferable primadonnas that won’t go onstage unless the dressing room contains live doves and a miniature woodland scene. My people will be in touch.

We were rewarded for our evening’s efforts by not one but two actual beds in not one but two separate bedrooms. If this luxury continues I might turn into one of those insufferable primadonnas that won’t go onstage unless the dressing room contains live doves and a miniature woodland scene. My people will be in touch.

I’m staying in Peckham with my old friend Alabaster dePlume. You may have heard of him, he’s on Debt Records. His album The Jester is one of my favourite LPs of recent times. He’s recently moved from Manchester to the South, trying his hand at life in the capital. Last time I spoke to him he was of no fixed abode, now he is living with the poet/artist Liz Greenfield – two dazzlingly creative people in one room, it’s a wonder the place doesn’t catch fire.

I’m staying in Peckham with my old friend Alabaster dePlume. You may have heard of him, he’s on Debt Records. His album The Jester is one of my favourite LPs of recent times. He’s recently moved from Manchester to the South, trying his hand at life in the capital. Last time I spoke to him he was of no fixed abode, now he is living with the poet/artist Liz Greenfield – two dazzlingly creative people in one room, it’s a wonder the place doesn’t catch fire.

I was on first again. It works better that way I think. I sing a bunch of songs about compromised morals and tragic inevitability then Felix cheers everyone up with romantic tales of unsnuffable optimism.

I was on first again. It works better that way I think. I sing a bunch of songs about compromised morals and tragic inevitability then Felix cheers everyone up with romantic tales of unsnuffable optimism. I watched most of Felix’s set from behind the door at the back of the room, occasionally flicking the Vs at him. It’s a great set, tonight was his best yet; he’s developing a brilliant routine of schizophrenic backchat with invisible soloists that I enjoy very much. Or that could just be the first stages of a malignant brain fever. We shall see.

I watched most of Felix’s set from behind the door at the back of the room, occasionally flicking the Vs at him. It’s a great set, tonight was his best yet; he’s developing a brilliant routine of schizophrenic backchat with invisible soloists that I enjoy very much. Or that could just be the first stages of a malignant brain fever. We shall see.

Felix and I are friends but don’t hang out much. When we do there tends to be a task in hand, we’ve not done a great deal of time-killing chitchat before. On the drive down from Manchester we discuss our bands, how fun they are but how difficult it is when members live in different cities, the fear of losing momentum, the need to keep going forwards but inevitably only at the speed of the least interested participant. We talk about how and why we started in this business, on which things we are prepared to compromise on and which ones we definitely aren’t; we talk about the musical he wrote and the one I’m currently writing (both involve the deaths of pretty much every single character – what has made us both so morbid?). The subject of ambition is raised and this is the point on which we differ most – Felix is aiming for the full Freddie Mercury but I don’t think I could stomach that, not anymore anyway, I just don’t like other people enough to have them all knocking on my door (I’m opting for the Ivor Cutler approach: a sizzle of notoriety and the bemused esteem of my peers followed by an obituary published ten years after everyone decided I was already dead).

Felix and I are friends but don’t hang out much. When we do there tends to be a task in hand, we’ve not done a great deal of time-killing chitchat before. On the drive down from Manchester we discuss our bands, how fun they are but how difficult it is when members live in different cities, the fear of losing momentum, the need to keep going forwards but inevitably only at the speed of the least interested participant. We talk about how and why we started in this business, on which things we are prepared to compromise on and which ones we definitely aren’t; we talk about the musical he wrote and the one I’m currently writing (both involve the deaths of pretty much every single character – what has made us both so morbid?). The subject of ambition is raised and this is the point on which we differ most – Felix is aiming for the full Freddie Mercury but I don’t think I could stomach that, not anymore anyway, I just don’t like other people enough to have them all knocking on my door (I’m opting for the Ivor Cutler approach: a sizzle of notoriety and the bemused esteem of my peers followed by an obituary published ten years after everyone decided I was already dead).