One of the things I always tell students whenever I’m invited to speak at music colleges is if something comes along that changes the entire way you perceive your art or ambitions, go with it – let accidents happen and see what comes from them rather than doggedly sticking to whatever you thought was right when you started out. It may be a disaster, but in this business a disaster is better than nothing.

The event that taught me this was the Edingburgh Fringe Festival. And in this instance the accident was a literal accident – specifically a traffic accident. In June 2008 I was a late addition to the bill at a fledgling folk festival near Calaceite in Spain; I went there as harmonica and spoons player with John Fairhurst then ended up playing a late night solo set that went down really well. Two months later I got a phone call from the organiser:

“I’m promoting shows at the Hill Street Theatre in Edinburgh and we’re in a bind. The Fringe starts tomorrow and one of our acts has just been run over by a car. Do you have a theatre show and are you available to do it every day at 6pm for the next three weeks?”

These were the days when I said yes to everything. Of course I didn’t have a theatre show. Who has a theatre show?

“Yes, no problem” I replied, “see you tomorrow.”

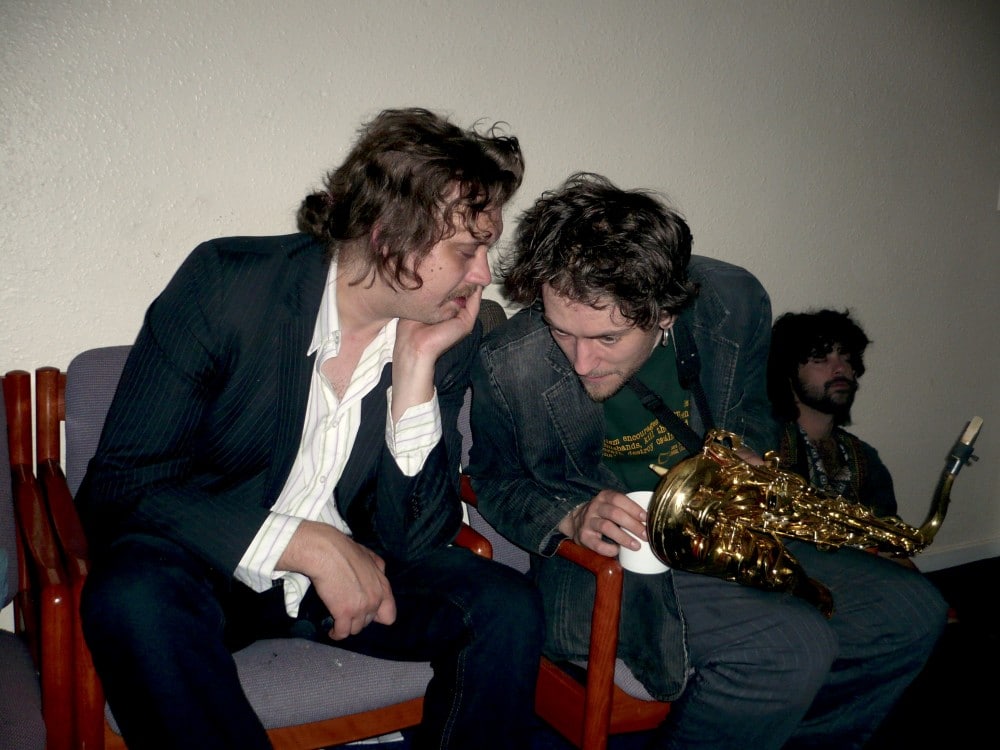

So I bought a train ticket with the last of my money. The direct service takes just over three hours and in that time I somehow managed to write a one-man show called Louis’ Lectures in Love – basically a dozen of my existing songs linked up by bitter rants about disappointing (fictional) relationships. I didn’t know it but this was to prove a massive turning point in my career. Was I a singer-songwriter or a character actor? In 2008 The Bedlam Six (then called The Black Velvet Band) was a pretty straight rock group; we’d just started to break through (or felt like we had) and were about to play our first festival mainstage. But relations were stretched, hope was getting thin and everyone was to some extent hedging their bets. I’d rung around my bandmates to see if they were free to do the Fringe with me. Ali had a week she could spare in the middle of the run, Cleg and Tom just a few days. Dan and Fran not at all (Biff wasn’t yet a member). I knew I couldn’t carry this on my own, I was already blagging it as much as I dared. So I got in touch with other friends from the Manchester music scene and by the end of the day had enlisted Richard Barry and Alabaster dePlume for almost the entire run, as well as John Fairhurst for a big chunk. The first two shows I did alone, then Richard joined me, followed a couple of days later by Alabaster, then John.

So I bought a train ticket with the last of my money. The direct service takes just over three hours and in that time I somehow managed to write a one-man show called Louis’ Lectures in Love – basically a dozen of my existing songs linked up by bitter rants about disappointing (fictional) relationships. I didn’t know it but this was to prove a massive turning point in my career. Was I a singer-songwriter or a character actor? In 2008 The Bedlam Six (then called The Black Velvet Band) was a pretty straight rock group; we’d just started to break through (or felt like we had) and were about to play our first festival mainstage. But relations were stretched, hope was getting thin and everyone was to some extent hedging their bets. I’d rung around my bandmates to see if they were free to do the Fringe with me. Ali had a week she could spare in the middle of the run, Cleg and Tom just a few days. Dan and Fran not at all (Biff wasn’t yet a member). I knew I couldn’t carry this on my own, I was already blagging it as much as I dared. So I got in touch with other friends from the Manchester music scene and by the end of the day had enlisted Richard Barry and Alabaster dePlume for almost the entire run, as well as John Fairhurst for a big chunk. The first two shows I did alone, then Richard joined me, followed a couple of days later by Alabaster, then John.

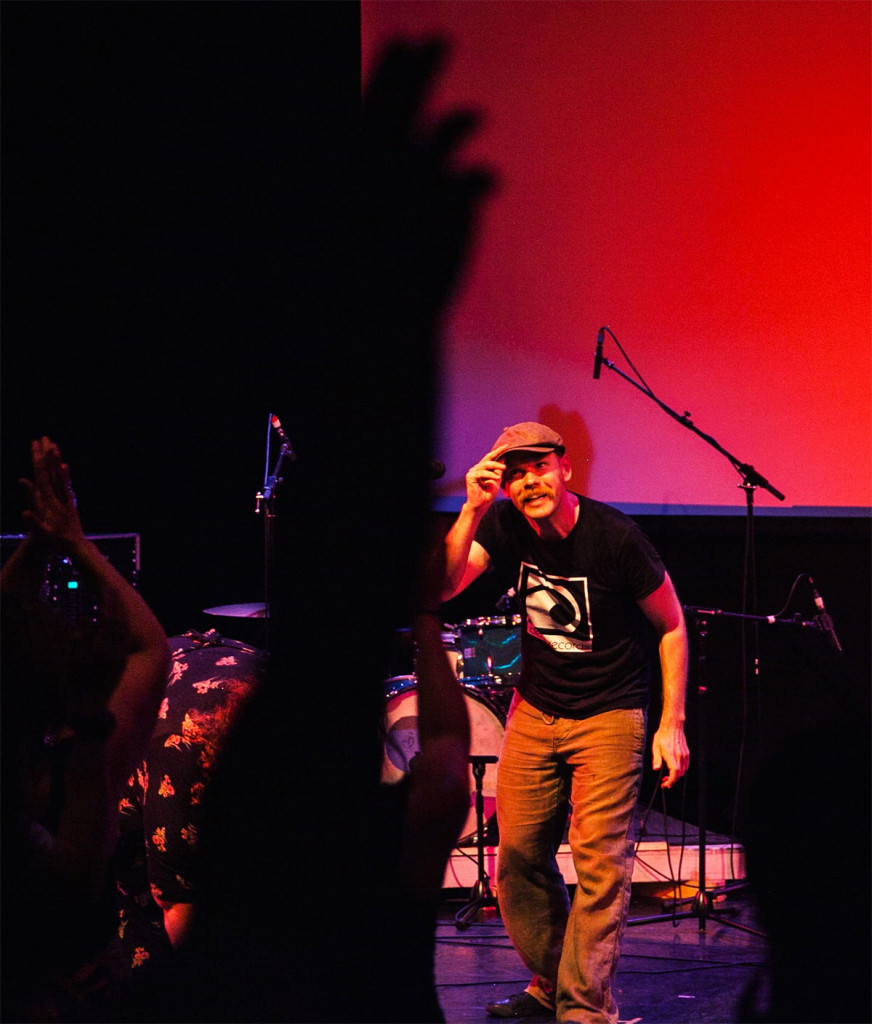

What happened next was interesting. We were all gigging musicians, used to being ourselves (or the inflated projected stage versions of ourselves) but faced with a sit-down theatre audience each night we quickly discovered alter-egos that suited this world far better. Looking back ten years later with a sober eye, what I think happened was a mixture of Bahktin’s theory of the carnivalesque (where one finds oneself in a temporary chaotically permissive bubble and changes one’s character accordingly) and Philippe Gaulier’s clown school in which one finds one’s inner clown through devastating emotional and physical exercises. During those three weeks we’d busk and flyer in the morning and early afternoon, then rewrite our show in the hours before curtain up, perform it at 6pm then play gigs for donations in the late evening. Money did not stretch far and we all lost weight. I remember coming to rely on shared morsels donated from the packed lunches of the theatre ushers.  We were also filthy: I had three white shirts in rotation and one suit. By the end everything was a grey brown, like we were providing our own sepia filter. But as the run continued and our free time became more of a blur, our little show gained focus. We didn’t want to just get away with it each night, we wanted it to be GOOD. Every night Richard, Alabaster and I tuned our characters and tightened up the changes, added shifts of beat and timbre, altered the narrative when joined by Ali, Tom, Cleg and John, then jumbled the ideas round when they left. By this time our friend Dexter had come along to provide tech support and we’d shifted from a loose cabaret feel to an actual story about dead performers trying to keep the lights on in the afterlife – a sort of musical Huis Clos. After two weeks of playing to tiny audiences (often numbering in the single figures) word started to spread that this was a show that changed every night and punters started to come more than once (and bring their friends). We even picked up an award from some obscure magazine. In the last week we were getting full houses and by the final two performances it was a show that finally felt right: it was alive, it worked and we really liked it.

We were also filthy: I had three white shirts in rotation and one suit. By the end everything was a grey brown, like we were providing our own sepia filter. But as the run continued and our free time became more of a blur, our little show gained focus. We didn’t want to just get away with it each night, we wanted it to be GOOD. Every night Richard, Alabaster and I tuned our characters and tightened up the changes, added shifts of beat and timbre, altered the narrative when joined by Ali, Tom, Cleg and John, then jumbled the ideas round when they left. By this time our friend Dexter had come along to provide tech support and we’d shifted from a loose cabaret feel to an actual story about dead performers trying to keep the lights on in the afterlife – a sort of musical Huis Clos. After two weeks of playing to tiny audiences (often numbering in the single figures) word started to spread that this was a show that changed every night and punters started to come more than once (and bring their friends). We even picked up an award from some obscure magazine. In the last week we were getting full houses and by the final two performances it was a show that finally felt right: it was alive, it worked and we really liked it.

And then it was all over.

I’ve never known hunger or fatigue like it. Never felt so dirty, like my clothes could stand up on their own. Never been so aware of friendships hanging by a thread. I was dangerously close to ruining my relationship with the Bedlams with this extra curricular activity and it took a long time to patch things up properly (not helped by a much-regretted vault of ego on my part that established the ampersand in our bandname from that time onwards). Living conditions were strained, there was always noise, there was too much booze (the barman at the theatre made the best Bloody Mary I’ve ever tasted), people came to our apartment for parties that lasted days and in comparison our show would feel like the sanest bit of the evening, like a precious gulp at the surface before sinking back into the slime. I remember one night Richard becoming so frazzled and furious by John Fairhurst playing guitar at 4am that he ran into the darkness of a nearby public park shouting “Who wants a fight? Someone fucking fight me!” Another night he stood in the wings stark naked while Alabaster and I played out a scene, strolling between the curtain pulls in my peripheral vision like the ghost of some poor grounded cherub cursed with human adulthood.

I’ve never known hunger or fatigue like it. Never felt so dirty, like my clothes could stand up on their own. Never been so aware of friendships hanging by a thread. I was dangerously close to ruining my relationship with the Bedlams with this extra curricular activity and it took a long time to patch things up properly (not helped by a much-regretted vault of ego on my part that established the ampersand in our bandname from that time onwards). Living conditions were strained, there was always noise, there was too much booze (the barman at the theatre made the best Bloody Mary I’ve ever tasted), people came to our apartment for parties that lasted days and in comparison our show would feel like the sanest bit of the evening, like a precious gulp at the surface before sinking back into the slime. I remember one night Richard becoming so frazzled and furious by John Fairhurst playing guitar at 4am that he ran into the darkness of a nearby public park shouting “Who wants a fight? Someone fucking fight me!” Another night he stood in the wings stark naked while Alabaster and I played out a scene, strolling between the curtain pulls in my peripheral vision like the ghost of some poor grounded cherub cursed with human adulthood.

I’ve not done the Edinburgh Fringe since. I’ve often been tempted but doubtless I would’ve made the mistake of planning too much – as the Bedlams got more successful I became more serious, saved the mayhem for the stage and stayed sober the rest of the time – it wouldn’t have been the same without the chaos. In 2009 Richard, Alabaster and I resurrected the show (now with an actual title: Dead At The Cafe Styx) for the Brighton Fringe, performing it in St Andrews Church; then a few months later we gave it one last run out in the theatre space above The Kings Arms in Salford (which I think was our best version – there was a bottle of red wine on stage that the three of us would each attempt to monopolise throughout the course of each scene; I also remember particularly enjoying the interval one night when we turned off the lights but didn’t bring them up again, just stood in the pitch black for fifteen minutes discussing how the first half had gone while the audience sat wondering if this was part of the show or if we’d just taken leave of our senses).

I’ve not done the Edinburgh Fringe since. I’ve often been tempted but doubtless I would’ve made the mistake of planning too much – as the Bedlams got more successful I became more serious, saved the mayhem for the stage and stayed sober the rest of the time – it wouldn’t have been the same without the chaos. In 2009 Richard, Alabaster and I resurrected the show (now with an actual title: Dead At The Cafe Styx) for the Brighton Fringe, performing it in St Andrews Church; then a few months later we gave it one last run out in the theatre space above The Kings Arms in Salford (which I think was our best version – there was a bottle of red wine on stage that the three of us would each attempt to monopolise throughout the course of each scene; I also remember particularly enjoying the interval one night when we turned off the lights but didn’t bring them up again, just stood in the pitch black for fifteen minutes discussing how the first half had gone while the audience sat wondering if this was part of the show or if we’d just taken leave of our senses).

But the place that birthed it: oh what glorious hell it was. That residency at the Edinburgh Fringe was what made me into the performer that finally managed to find a career in the music industry. Embracing theatre and character and painstakingly rendering chaos into a finely tuned nonsense, that became the Bedlam Six’s calling card for years to come. But more than anything it was the context that was the star. A big mess of performers throwing their money away, not looking after themselves properly, getting into debt for the sake of their art, hoping for a break, crying out for an audience in the most oversaturated performance space in the world. It’s basically a microcosm of the creative industries. And that’s why it is such a worthwhile experience: What doesn’t kill you makes you stranger.

But the place that birthed it: oh what glorious hell it was. That residency at the Edinburgh Fringe was what made me into the performer that finally managed to find a career in the music industry. Embracing theatre and character and painstakingly rendering chaos into a finely tuned nonsense, that became the Bedlam Six’s calling card for years to come. But more than anything it was the context that was the star. A big mess of performers throwing their money away, not looking after themselves properly, getting into debt for the sake of their art, hoping for a break, crying out for an audience in the most oversaturated performance space in the world. It’s basically a microcosm of the creative industries. And that’s why it is such a worthwhile experience: What doesn’t kill you makes you stranger.

I’ll leave you with the final line of the show, written and spoken by Alabaster as the lights fade to black:

“If you keep digging the same hole… it only gets emptier.”

There are some events that you just can’t see past. They loom on the horizon, impassable, immovable and as dubiously perilous as Don Quixote’s windmill giants. The

There are some events that you just can’t see past. They loom on the horizon, impassable, immovable and as dubiously perilous as Don Quixote’s windmill giants. The