Sustainability is the biggest buzz-word on the circuit at the moment. Not just in music circles, it’s a hot topic in every industry.

When I’m invited to speak on panels this is the subject I’m most often asked to comment on: How To Build A Sustainable Career In Music. Well, that subject is going to get its own article one day (or perhaps a book) but for now I thought I’d write a little piece about the first thing that suffers when one is wrestling with the finer points of a so-called-sustainable self-managed independent music career…

The Writing.

When we talk about sustainability at music industry events it’s almost always placed firmly in a financial context rather than a creative one (usually stuff about corralling people from social networks into online stores, keeping touring costs down etc). But there’s a persistent worry I’m having trouble ignoring: In the early days of the band (and prior when I was a solo artist) I wrote about twenty to thirty songs a year – two or three a month. Some good, some dreadful but all songs. Fast forward to now: we’re half way through August 2012 and I have written two and a half songs. Last year I think I wrote five.

Of course there could be all sorts of reasons for this. Indeed, my “bullshit filter” is far more stringent these days, I kill my weakest offspring early to give the other fledgling ideas a fighting chance; I have more experience in this field now and am able to predict the compositional dead-ends before I crash into them headfirst – I can (to plunder a term popularized in Hollywood westerns) “head them off at the pass” when the horses of my imagination start galloping blindly towards a canyon. I am also older now, everything I do is a little more considered.

Explanations aside, however, I can’t help but mull over the fact that most of the songs on both my upcoming solo record and the band’s next LP were written in the same prolific burst that followed our first album’s completion in 2008. I feel like I’m doing a Noel Gallagher, living piecemeal off the squirreled-away creative fruits of sunnier times.

I’ve been thinking about the act of writing a lot recently (when really I should be getting on with some ACTUAL writing). The other day my friend Kirsty Almeida asked me to collaborate with her on a (typically insane) project called Thirty Songs In Thirty Days – a kind of dare/bet/torture she had set herself whereby she (you guessed it) writes a new song every day for a month.

So I went over to her house to write a song, with not so much as a tune in my head to get things going. My friend Alabaster dePlume was also there. Like me Alabaster is a very private writer, we sometimes share our early drafts and first verses but never ever when they’re still at the embryonic stage – it is easy to bare one’s skin but never one’s bones.

None of us were in our comfort zone that day. We took a theme from a list of random words suggested by Kirsty’s social media feed (choosing “Glove” – ripe for innuendo) and got to work. Early on Kirsty suggested we break the ice by taking it in turns to make up a line on the spot and sing it into a microphone, going round the circle a few times then picking out any potentially good ideas from the recording and building on them subsequently. As a rule I find such activities petrifying (in a near-literal sense of stony social paralysis), putting me in mind of the rainier recollections of scout camp and other hellish group activities that are supposed to be character-building or confidence boosting but can also lead to repressed memories, latent schizophrenia and Herbert Lom-style facial spasms.

Somewhere there now exists a recording of Kirsty saying (in her best Nurse Ratchet voice) “it doesn’t matter what the lyrics are” and me sulkily muttering “it always matters what the lyrics are…”

But of course it all turned out fine and once the three of us relaxed into a working rhythm that suited us all we had a great time. I’ve talked before about the importance of getting outside of one’s comfort zone as well as how valuable (and indeed essential) it is to collaborate with others – I’m glad to report that on both counts this experience was highly rewarding.

And it was great to get a rare glimpse of the way others compose. In my work with Un-Convention I spend time trying to demystify elements of the music business to help emerging artists (and indeed myself) find a path that suits them/us best. One of the greatest myths we struggle with in the creative industries is, perversely, that of creativity itself. It is almost as if artists are sworn to an oath of secrecy like conjurers in the magic circle. Now, as a performer I am well aware of the value of myths and magic and I certainly do not welcome transparency in all areas of what I do (and I’m sure the audience wouldn’t either) but I am happy to admit that there is no great celestial process, I do not rely on a muse and no one I know has ever sold their soul at a crossroads.

I suspect a lot of artists are preoccupied by other people’s creative process. That’s the impression I get when I see the way in which many examine the work of certain practitioners as if they’re attempting to decipher an ancient language. But much of the time there is no process – there are just songs, each one requiring a different treatment, there being as many variants as there are illnesses. Imagining that others have some kind of procedure while the rest of us go blundering along hoping to trip over some amazing fully-formed idea is nonsense. Apparently Dylan and Bowie both cut out random words and arranged them in different combinations when composing their lyrics; Leonard Cohen whittled Hallelujah down from eighty draft verses over many agonizing months; Lennon and McCartney would bash away at an idea for three hours and if they hadn’t finished it in that time they’d move onto something else, if hook lines didn’t survive in the memory for twenty four hours unaided by recording or notation then they were deemed unsuitable for development. All these are examples of legendary song-writers, all with different ways of working. And, quite possibly, a lot of that stuff isn’t consistently true. After all, do any of the above really seem like the kind of personalities that would follow strict rules?

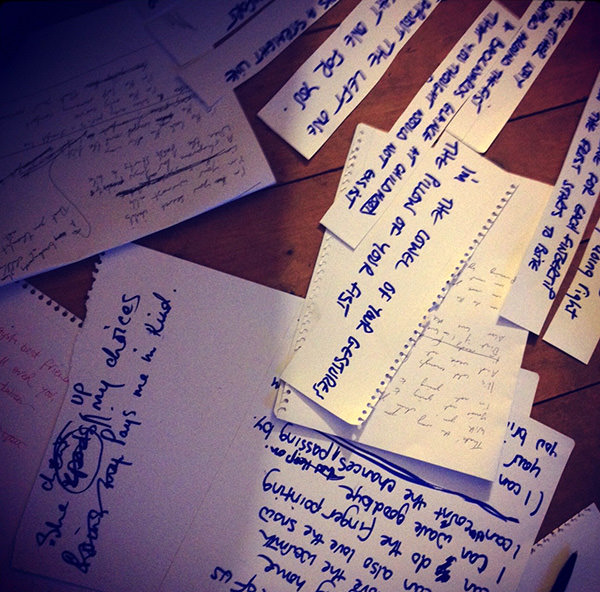

Personally I write absolutely everything down immediately (in near-illegible tiny writing so as to save paper – see photo with guitar included for scale). It is an almost compulsive thing. So I guess that’s my technique. I archive each lyric-shaped thought, quip, couplet, metaphor and observation. Walk a lot, watch a lot, fill up the notebooks and hope I’ll make sense of all that accumulated human data later. But when it comes to finally forging the pig-iron into steel there’s very little science involved, in fact every time I write a song I feel like it’s the first one – and not in a romantically innocent way, more in a “what the hell am I doing” way. I don’t have much recollection of how I wrote the last one because, as a rule, after they’re finished I make a concerted effort to distance myself from the thing and listen from the point of view of an audience. Simply put I think the unifying factor of each piece is that I try to follow what I think a song should do from one point to the next without much thought given to technical theory, instead I go with my gut (this isn’t a conscious decision – I’m just not musically educated so it’s the only option left open; admittedly I think being relatively naive in this regard can sometimes be an advantage over more trained ears, though many would disagree with me).

I generally get the emotional shape of the song in my head and then hack away at it until it makes narrative sense. After the original ideas have happened the actual rendering of them into something singable definitely feels like work rather than pleasure, in all but the rarest of cases I end up with a bastardized (indeed compromised) version of the original concept, like when Victor Frankenstein assembles his creation from the best bits he can find on his midnight walks only to find that together the pieces form something grotesque. But it can be difficult to get a sense of the whole thing when you’re concentrating on the details. At times I feel like I’m working on a tapestry in the dark with oven gloves on. See, I’ve already made my songwriting metaphor leap from smelting to sculpting to grave-robbing to needlework. But then I’ve made a career out of such inconsistency (my creative barometer has always fluctuated between “high pressure” and “risk of storm” – oh there’s another one).

But the reason I am writing less now is not due to my rather slap-dash methods or a dearth in material, it is simply that I no longer put aside as much time for working through my notes and hewing them into songs. Somehow firing off endless emails to promoters who are not interested in booking me has become more valuable than investing the hours into what is, essentially, my product. I still write everything down, my little A6 unlined pocket books still fill up at the same rate, the people I encounter on a daily basis in shops and banks and buses show no sign of becoming less preposterous – inspiration is certainly not dwindling. The difference is that I now spend more time on the computer and phone than I do on the guitar. I just don’t empty my head as often and look at the world askance (askance being the optimum tilt for my preferred species of songwriting).

Since I went full-time at this I have found the role of artist-manager to have more in common with a caretaker than a creator – one spends more time maintaining existing things than building new ones. As important as sustainable touring and low-budget marketing is to an independent musician sooner or later this basic neglect of the roots of one’s vocation is going to cause real problems. To prevent such a deeply penetrating rot taking hold it is essential to maintain some degree of equilibrium between art and admin.

My advice: Don’t be concerned with writer’s block. Be more concerned with writer’s balance.