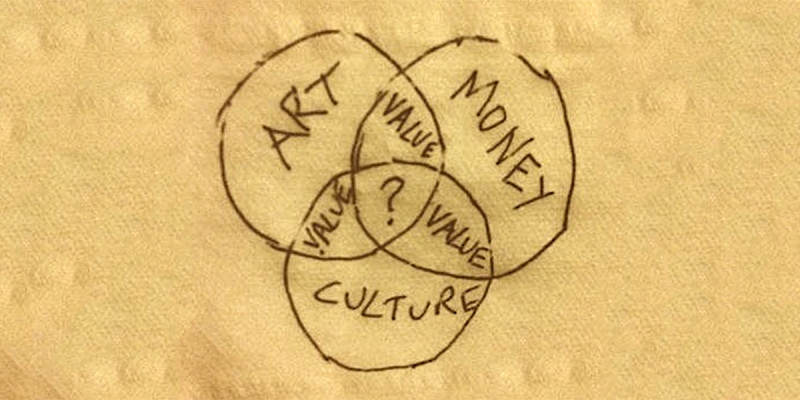

Last month one of my articles was published in The Cultural Value Initiative. It wasn’t until they got in touch that I realised “Cultural Value” was a subject I’d been writing about regularly since 2010 (I just thought I was venting some spleen).

Maybe the reason that particular article was picked up was because I finally found the courage to talk about the internal battle raging (in varying degrees of fury) inside all professional and semi-professional musicians: Art versus Money.

That piece mostly concerned itself with live performance. I’ve been thinking more recently, however, about the recorded side of things, particularly the ever-evolving relationship between consumer and product – the rapidly fading desire to actually buy a band’s release in a world where various online streaming and cloud subscription options are becoming more available, affordable and practical.

This subject is particularly on my mind because next week I’ll be burying myself in a studio for the best part of a month with a bunch of obscenely gifted ruffians to record a “difficult second album”. And though selling an indecently large quantity of the finished product is not my primary motive for making the thing, out of all the reasons for doing so it definitely makes the top ten.

It’s an interesting subject. Notions of monetary value always depend on comparison and context – the comparison between products and the context of the purchase. I don’t buy bottled water because I’ve got a tap in my kitchen – but the other week my apartment block suffered a burst pipe and we had no water for three days, funny how quickly one rethinks what’s important.

Somewhere down the line we reached a point where the value of recorded music came into question. But only it’s monetary value… not it’s cultural value. Culturally it is still a goldmine. Politicians still seek the approval and endorsement of pop stars, as do multinational brand names and business tycoons. Every day people communicate with each other on social media platforms by posting links to music videos. Levels of cool are still judged in some part according to music taste. It seems that the value of music is not in question at all. Just its price.

I’ll wager that a formidable chunk of this article’s readership will have on their computer an illegal copy of a song they absolutely adore, one they are regularly moved by. Throughout their day they may listen to it while frittering away their money on cans of coke and fast food and celebrity gossip magazines and a zillion other examples of utterly transient flotsam that our society makes us wade through on a daily basis. Yet they will not pay 79p for a song that makes sense of their life. And if the cost was 10p they probably still wouldn’t. It is the priceless soundtrack to a vacuum, the glittering frame to an empty canvas. Why the coke and not the song? Does this come down to a feeling of entitlement where one thinks of music the same way as I think of what comes out of my kitchen tap? Essential yet abundant?

Yes, it’s in my interest for people to believe in remunerating artists. But believe it or not I’m not that concerned.

Because I’m not even sure if this is a problem. Maybe it’s just teething pains. Yes it’s undoubtedly a worry for a lot of people. Indeed, all the money that my band is spending on making this new record comes from sales of the last one. If no one buys this one then there won’t be another one. It is a cycle that, even before factoring in the living costs of those participating in the recording, is not even self-sufficient without some sort of record buying market, no matter how niche.

But one thing I don’t think will save the recording industry is snarky Facebook memes about “people who are happy to buy an overpriced cup of Starbucks coffee rather than buy an amazing song at a quarter of the price”. I see these things every day. “You wouldn’t ask a plumber to work for free” is a common one (what is it about plumbers that makes them so popular among people trying to make a point? Remember Obama and McCain talking about Joe The Plumber? Amazing to witness a man becoming a metaphor in real time. Cringe-inducing stuff). Another favourite is “when you pay for a gig ticket you aren’t just paying for an evening’s entertainment, you’re paying for years of rehearsal, equipment costs, petrol etc…” What utter rubbish. You can’t compare music to coffee or petrol. You can’t break down the value of art into the amount of years spent practicing the guitar. I have been moved by old masters and young chancers in equal measures. If you start applying these kinds of measurements to creativity then the world will become more impoverished than ever before. How much did that art move you sir? Three feet? Four and a half? Would you say the level of inspiration was more equivalent to Elvis or Debussy?

Maybe the reason people are buying less music is that we have upgraded (or downgraded) it from product to currency. Maybe what was once called pop music is now just part of the language. When we flounder for some way to express ourselves or make a point we reach for google and bring up a song. Perhaps it is just the next chapter in the natural evolution of the cliché.

And some will say (as they always do) that the internet is to blame. That we’re in this situation because of the Napster free-for-all of 1999. But this change was inevitable – it is merely one set of artificial price-tags replacing another. The moment where the distribution of music was finally wrested from the grip of the established labels was inevitably going to create a lot of debris and noxious fall-out. But while the internet brought with it a digital battering ram to flatten the traditional gatekeepers it also gave people a relationship with the artists who made the music – at least to those artists who make themselves available to relate to. It is no coincidence that the artists who measure their product on the same scale as Starbucks coffee are doomed to obscurity. Starbucks’ coffee, overpriced or not, is sold in vast quantities because its presentation and delivery fits well with so many people’s daily routines. Context again. The way successful independent artists market themselves has more in common with the independent cafes whose success or failure depends on word of mouth and projecting an appealing personality. They are a bit less convenient but also a bit more rewarding. The ones who respect and cherish their audience and foster a meaningful relationship with them eventually attain something approaching a sustainable career; the ones who don’t tend to be bands that spam you up to the eyeballs with their wretched Kickstarter campaigns.

It is a shame that so much of what we are faced with in today’s DIY sector comes at the hands of chronically unimaginative bores dreaming up whimsical facebook memes about what music is supposedly worth (Gershwin’s Summertime presumably is equivalent to, say, eight years of piano lessons and a season ticket at the local concert hall – strange, I would’ve priced it a lot higher) while the supposed bright young things of Rock spend all their time impersonating the worst kind of needy salesmen – “hey, listen to my new song, download and share!” has never sounded so much like “good afternoon madam, if you’ve had an accident at work you maybe entitled to compensation…” As culture goes, I’m struggling to think of one with less value. But that’s the other thing about the internet: never has mediocrity been so visible. In the end, when some future Hobsbawm writes the book about The Age Of Memes, some artists will be swallowed up in the chapter about facebook malpractice and others will be in the chapters about music and culture.

And that’s just it. Our notions of value only exist within their cultural parameters. If we are talking about what something is worth then 10p is not much for a great song. £1 is also not much for a great song. One could argue that £1000 is not much for a great song if it changes your life for the better. But these terms are completely inadequate. Could you put a price on a favourite memory or a first kiss or a unique combination of sunlight and shadow on a crisp October morning? Good music has more in common with those things than it does with what one would or wouldn’t pay for a cappuccino. Notions of cultural value shift with every ebb and eddy of human activity, but there is a fundamental worth intrinsic to the very phenomenon of music that remains constant. Society always finds a way to put a price on the things that inspire the most joy and, in turn, people always find a way to get those things for free. It is a cycle as constant as the rotation of the Earth. That is our culture, one that has been around far longer than the fashion of measuring its value.