If I were to say “I’m writing a novel” I expect people would mostly respond with “What is it about?”

When I mention I’m writing a musical, however, the most common response is “Do you have funding?”

Maybe it’s just the company I keep. Almost everyone I know seems to be in a constant state of application angst, totting up projected expenses for arts council bids, bombarding their social media feeds with kickstarter campaigns, trying to work out if there’s any kind of community outreach slant they can put on a new project so that it meets the criteria for some glittering new grant…

I’ve been avoiding the funding question ever since I started this musical. Though I will certainly do my best to secure the budget for a full-scale production when/if the time comes (or at the very least a soundtrack album) this project was always designed to be for me. I want to finish writing the thing before I think about selling it – just seems more sensible that way round. This is my hobby away from all the admin associated with DIY labels and DIY music careers. Those two things were supposed to be glamorous enough to balance out the mundanities of British life. But everything becomes normal if you let it. And I let it. I wrote about three songs last year in between doing the booking and PR for Debt and The Bedlam Six. Then when I started working on the musical I wrote sixteen songs in eight months. I feel completely rejuvenated.

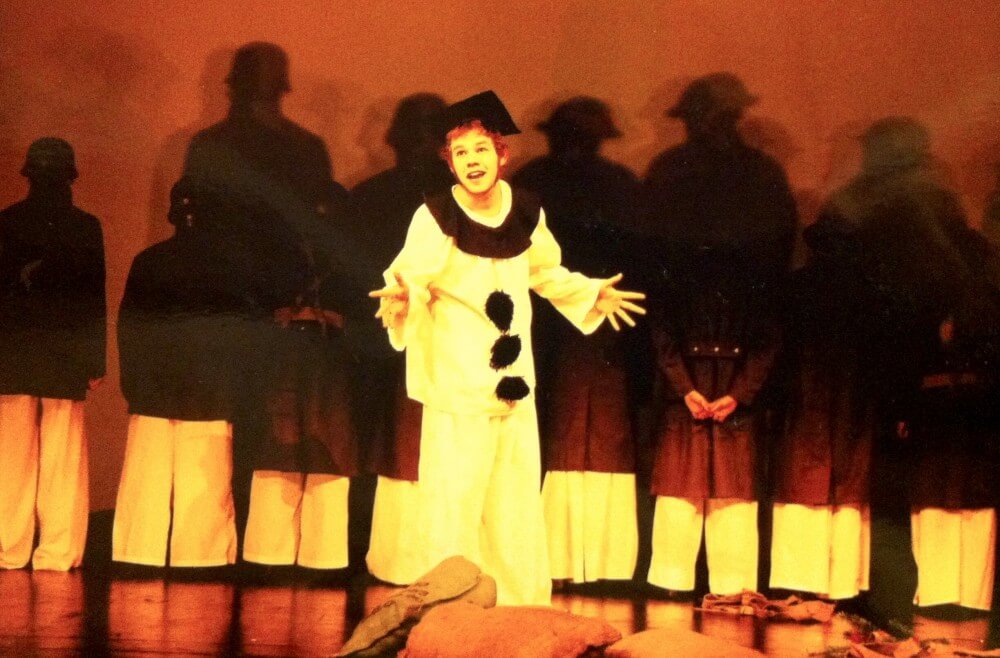

I’ve been talking about writing a musical for over a decade. My background is in theatre. That’s me in the photo above, playing the MC in Oh What A Lovely War. I love the artificiality of theatre. I love how the audience is in on the deception. Pop music would be much the same but for the fact that everyone involved is generally trying to con everyone else – critics and audiences are forever discussing the idea of artists laying themselves bare, of uncovering truths, of expressing their feelings when most of them are only peeling off one mask to replace it with another (similar to what we all do in everyday life I suppose). Imagine going to see A Midsummer Night’s Dream and discovering that the person next to you actually believes fairies have replaced a man’s head with that of a donkey’s. You’d say “no, look, you can clearly see it’s a costume” as they rock back and forth gabbling incredulously. Then go to a music venue and watch the strutting geniuses emoting furiously into their microphones for a nice tidy ninety minutes, the front row swooning into the arms of security guards. Theatre isn’t the only place that’s full of asses.

The second most common response to me mentioning my musical is “Oh I must admit I’m not really that keen on musicals.”

Well I must admit I’m not really that keen on BAD musicals either. Musicals used to be churned out with the conveyor-belt regularity of B-movies and spam. But the good ones, the REALLY special ones transcend time. Productions like Singing In The Rain, Oliver!, Cabaret and The Blues Brothers have little in common but share one key attribute beyond the use of songs – they are all about periods of transition (in these instances struggling severally with modernism, technology, political ideology/extremism, poverty, exploitation, popular culture and redemption). This is what the musical excels at – those absurd, almost surreal explosions into fantasy throw a warped reflected light on the real life that spawns it.

People aren’t all that surprised I have ambitions in this area. Most reviews of my work mention theatricality (some positively, others less so) and I was initially under the impression that writing a musical would be a way of giving that side of my brain free rein for a while, to really indulge the ideas that would ordinarily be scoffed at by the po-faced music press as overly self-indulgent. Once I got going, however, I found that I was being more drawn towards a conventional pop bent – writing quickly and simply, not over-egging metaphors or trying to be showy or clever. Songs about one thing, one thought, one idea – statements of intent or reaction rather than the self-reflexive peregrinations I’m often guilty of. Perhaps one of the reasons I’m finding this project so liberating is that there is very little irony at work. Most of the songs I write for the Bedlam Six contain a hefty dose of cynicism, indeed I tend to embed the seeds of a song’s undoing within the song itself, probably as an unconscious way of deflecting criticism. But here there are characters that have their own ideas; my go-to cynicism does not fit with the dreams and opinions and ideologies of this cast of characters, they’ve got bigger worries than me. It’s been quite an invigorating experience writing songs about optimism. Besides, there’s no need to temper a song’s hopeful resonance with doubt, the events that follow will provide their own ample balance soon enough – some songs are light, some are shade, there’s no need to be overly academic when dealing with the spectrum of emotions. And for once it’s not all about me. Indeed, one of the reasons I wanted to write a musical was that I longed to create something that could stand on its own two feet. Bedlam songs are only songs when we play them. They’re like trousers and shirts, they don’t look like anything when they’re not being worn, just a flop of rags. I wanted to make something more like a hat or a pair of shoes – something that keeps its shape, something that doesn’t need me to inhabit it. Something that I can ultimately walk away from – or indeed something that might walk away from me.

So what is it about?

This is where the eyes start rolling.

My musical centers loosely on the story of Oedipus (by the way, the third and forth most popular responses are “Does it feature your song Mother?” – no, that song actually has nothing to do with mothers – and “have you heard Tom Lehrer’s song about Oedipus?” – yes, but I think after sixty years the rest of us are allowed to have a go at that subject without upsetting the culture police). There have been a handful of attempts to make this story into a musical over the years, mostly small-scale fringe productions playing it for laughs. The fact that the typical reaction to the Oedipus myth is one of amusement just goes to show how horrifying we must all think it is. And it is for that reason I wanted to tackle it. And not as a comedy. This is arguably the greatest of all the tragedies – nowhere else is the concept of Fate as universal villain so utterly, irredeemably, ruthlessly hideous.

Oedipus himself is a pretty tedious protagonist though. So passive. That’s why I’m concentrating on Jocasta, his mother. She is just as cursed as he is, more so even. The version I’m writing focuses on her transition from naive trophy bride to reluctant steward and finally to powerful doomed regent. She is very strong and she is very flawed. There are a lot of songs about hope. And, inevitably, hope dashed. It’s set in a sort of alternative 30s Britain, kind of like if we’d had the Spanish Civil War here. It’s a bit of a historical/cultural smorgasbord though, I’m keen to throw in a more contemporary view of politics and spin doctoring, the classical Greek Chorus in this instance being members of the gutter press and braying backbenchers. It’s all going to be pretty bleak and I doubt Cameron Mackintosh will be knocking on my door any time soon.

But just because we’re all going to die doesn’t mean we can’t make a song and dance about it.

In fact there’s every need to make a song and dance about it.